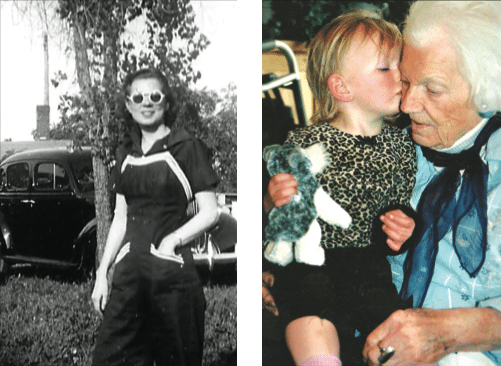

Photo courtesy Sherman Wick

A chunk of snow falls while my grandma Dorothy Marie Miller Wick Rangitsch Hayes stares out the window. She is eighty-nine years old and lives in the disorientation and terror of dementia. During a February thaw another chunk breaks off the eaves, crashing with a boom. Suddenly coherent, she asks, “Johnnie, how’s the house on Searle?”—the house where she grew up in Saint Paul’s Payne-Arcade neighborhood. We’re sitting in a nursing home in Hudson, Wisconsin, and Johnnie—her only son and my dad—died eight years earlier.

I’m Sherm, the namesake of her first husband and father of her four children. Sadly, she outlived three husbands. The emotional trauma of past tragedies exacerbate her vivid nightmares—so posits the social worker—that increasingly creep into brief windows of wakefulness, consuming the happy-go-lucky grandma and transforming her into a confused and cowering child.

Momentarily, I converse with my grandma, who is loquacious again. In recent years, she has spent her days in bed or in a chair crying and sleeping. The warmth in her face returns (“I’m glad Aimee’s here”), as does as her jocose manner (“She’s a good girl when she’s sleeping”). With white bouffant hair still piled high, she smiles, displaying her one good tooth. Astrid, my daughter, bounces on my lap. I nod at Grandma; my sister Aimee is a social worker at another nursing home. Grandma believes it’s still the early 1980s. Back then she initiated our exploration of the Twin Cities, taking me to Twins games and practically every park in Saint Paul—where she’d grown up during the Depression playing tag and kitten ball while her Scottish-immigrant father worked on the railroad.

Listening intently, Grandma asks about the yellow house between Edgerton Street and Payne Avenue. “I’m sure it looks swell. Dad’s a hard worker. . . . Stop by on the way home.” I nod, even though my dad resided near Stillwater, and my great-grandpa died before my birth.

“Remember, Johnnie—follow Payne to Ivy Avenue then to XXX Searle. I’m taking a nap now.” An ache runs down my spine. As her eyes close, I wonder, will she ever be this lucid again?

Driving home to Minneapolis, we take the long way through the East Side, the way Grandma would: up Payne Avenue, eventually finding Searle, the block platted by Olaf and Dagmar Searle, Norwegian immigrants, in 1887. This is it. My throat tightens. “Astrid, Grandma lived here when she was little.”

“Grape-grama little,” says my four-year-old. “No, grape-grama old,” she says, shaking her head incredulously.

An Asian American man shovels the yellow house’s snow. Driving away, I imagine a Hmong American family in the ancestral home. Grandma would be happy: another immigrant family pursuing the American dream.

Grandma was never that coherent again. But occasionally when I’m sad, I take the long route—as Grandma did—to XXX Searle. I close my eyes: she’s a little girl playing hopscotch.