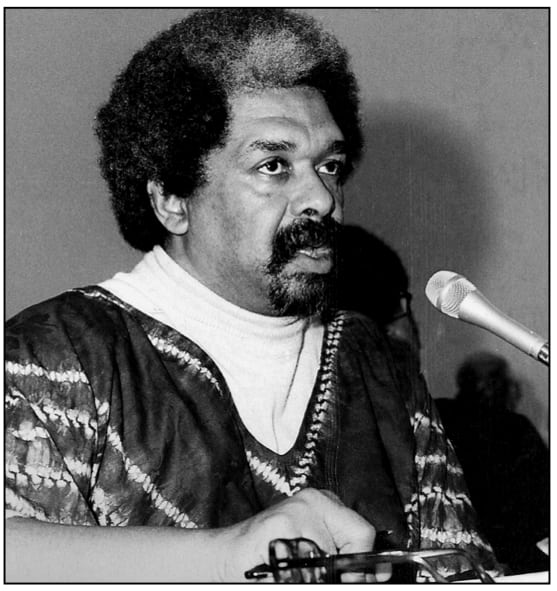

Kwame McDonald, an African pillar in the Saint Paul Rondo community, was working on his autobiography when he transitioned into ancestorhood. I had the honor and privilege to work with him and hear many of his stories and his Wize Owl wisdom. I really didn’t get to know Kwame until the last five years of his life. While growing up in Rondo, I only knew of this man from a distance as one who seemed to always have on a dashiki and kofi with a camera around his neck at sporting events. I finally received a deeper glimpse of him on January 1, 1988, on the Day of Imani during a Kwanzaa celebration at the Inner City Youth League. Kwame and many other African elders shared with us neophytes the legacy and dream of our community. This being my first Kwanzaa celebration, it would prove to be a critically consciousness-raising and mind-altering experience for me. As we say, “The elders dropped some serious knowledge on us that night.” One of the mind-blowing experiences that evening was at the end of the celebration. Kwame took this huge red, black, and green African liberation flag down from the wall and brought it to elder Niama Richmond, asking her, “Can you make me something from this?” She replied, “Oh yeah, I can make a dashiki for you.” Kwame looked over to me and said, “You see, I only wear clothes made by my people.” Sadly, I wouldn’t have the follow-up conversations with him regarding his profound statement until twenty years later when we worked on some educational initiatives together and we began to work on his book.

Below is the opening essay of Kwame’s book, which will be forthcoming. For those who knew him, this essay is what I would often call “Classic Kwame.”

We were fine, thank you

Kwame McDonald

Growing up Black was so much fun! My brothers, sisters, and I never knew we were poor. I was taught that in Sociology 101, in college. I am sure that they, my three brothers and five sisters, learned the same in their first years in college.

We have never discussed this—our so-called poverty, that is. When my first father died, I was glad that my grandmother would not let my mother go on welfare. My two uncles and two aunts helped my mother and grandmother ensure that we would be free of government intervention.

Soon, my mother married my new father. He was never a step-parent. His penchant to serve and save his children was obvious. He not only worked a full-time job and several part-time jobs, he also hired us, his children, to help clean bars, barbershops, stores, beauty parlors, and apartments.

We never heard that we had financial problems. The simple fact that we had so much love from our whole family and neighbors rendered us wealthy. To put more details to this story would only serve to romanticize a very ordinary life experience among Black families in Amerikkka. I hope nobody ever talks about our family as one who overcame alleged hardships, financial

challenges, and so-called poverty.

Fortunately, money, acquisition of “things,” and the compilation

of “stuff” never did define our lives. While others, I am sure, viewed us with pity, sympathy, and empathy, we were then, as we are now, quite a happy family of high achievement and service providers to the communities in which we live. As we move to assist others, remember, it is not what we give them. It is how we helped strengthen our own power and ability to positively serve others and self.

Author’s note: Amerikkka is a term used primarily within the African American community’s prophetic tradition since the forming of the Klu Klux Klan in 1865, the year ending slavery in the United States of America. In African American Vernacular English, this term denotes essentially the concept that white supremacy is as American as apple pie and baseball. Racism was a major part of the founding of America and sanctioned by all our legal and trustworthy institutions. Activists, in the Black churches, Nation of Islam, and several in the movement for justice in general, used this term to denote that in modern times America has made progress toward equal and just treatment of Black people, however, she still has deep-rooted systemic discrimination that doesn’t allow the healthy development of many communities, in particular the Black community. Thus, this term was/is not meant to be derogatory, but rather a metaphoric description expressing the duality of America’s beautiful and yet painful past and existence.