© St. Thomas Photo Services/www.stthomas.edu/photo

Saint Paul is my chosen home, the place where I feel most deeply that I belong. Now. It has not always been so.

In many ways my story is similar to countless American’s; we are, as President Kennedy wrote, “a nation of immigrants.” But

when I arrived in Minnesota—my nine-year-old head swimming with tales of American opportunity, green cards already waiting—I felt extremely disoriented, almost as if I’d been kidnapped. My father, a dry grocer and merchant in Mafraq, Jordan, had come over two years earlier, working two jobs until he could bring the rest of us. Mafraq is a Bedouin town near the Syrian border; its name means crossroads, an apt description of its centrality on the road between Damascus and Amman. I had arrived, against my will, at an entirely different kind of crossroads.

We’d landed at O’Hare, my mother and the seven of us, and all the way to the Twin Cities, our earthly belongings strapped to the roof of my dad’s Dodge Colt, I felt everything I knew falling away in a swirl: not just familiar desert architecture and landscapes, the palm trees and camels, but all the tastes, smells, colors, and sounds of my young life, all slipping away as we headed northwest across the alien prairie. In the suburb that became my first American home, we were the only family of color for as far as my legs could walk in any direction. It was a difficult experience for a long time, breathing in and slowly taking up a new culture and home.

But when I went back to the Jordan I’d so ached for eleven years later, I found I was now a tourist in my country of origin, soaking up sites I’d never seen as a child. I couldn’t get enough—visiting Petra; splashing, wading, and bobbing in the Dead Sea; a day at the ancient Roman-ruin amphitheater in Jarash—but even then villagers called me “the American,” pointing out subtle differences in my dress and manner that marked me, even if I was unaware of them.

Innumerable nuances of culture and circumstances have carried me to this place where Minnesota’s crossroads city, its capital, feels so thoroughly my home. Saint Paul is urban while being historically interesting, with its distinctive buildings and neighborhoods, its growing diverse cultures living together while retaining important features of their countries of origin. I created my coffee shop where people who trace their ancestries back to Minnesota territorial days mingle and feel at home with those recently arriving from other places and histories. All contribute to my sense of belonging here. Now.

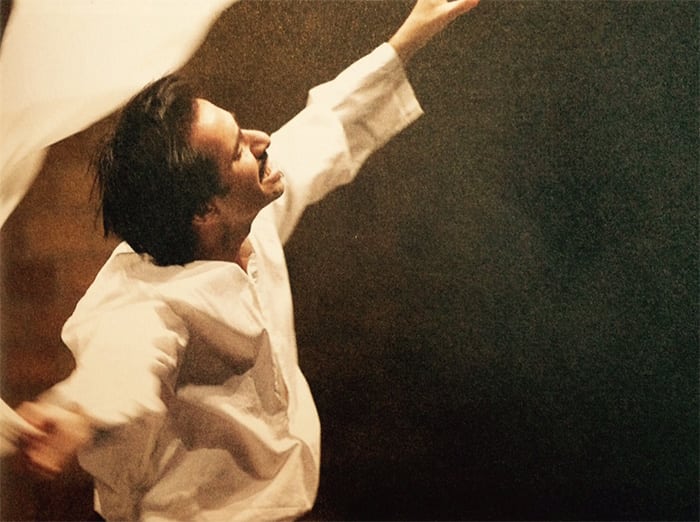

I’ve always done traditional Middle-Eastern dances at family celebrations, but an experience I had more than a decade ago, the first

time I performed on stage, helped me recognize I’d been reborn in this new place. The performance began with six of us dancer-actors,

each from a different homeland, laying flat on the stage, hidden under a large sheet of white fabric. After slow rhythmic stirrings, each of us emerged to tell his or her own story in that darkened auditorium. Something about that narrative-dance, a blend of traditional Arabic dance and my own invention, that movement from private act to public dialogue with a random audience, made me understand how much at home I was here in this new crossroads; now so many things had come together to make me belong.

Toward the end of our performance we sat under a tree on stage and drank coffee together, always a sign of community in Jordan; we ended with a joyous dance. My life in Saint Paul is not a joyous dance; no one’s is. But this crossroads is where I now belong.