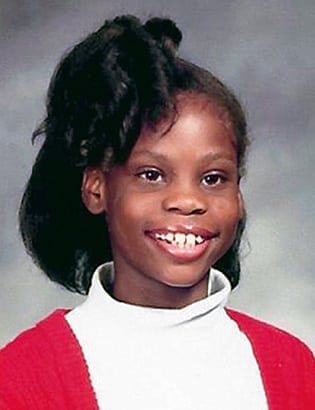

Courtesy Maya Beecham

I was seven years old, in second grade, and tired on a daily basis.

Most mornings I arrived at Highland Elementary School after limited sleep. I was robbed of sleep by bouts of eczema,

an inflammatory condition of the skin. Rashes covered

my skin, and in the middle of the night, half

asleep, I removed the socks from my hands and

dragged my wirey fingers and fingernails against

my dry skin, scratching for relief that seemed

unattainable. Endless scratching led to long mornings.

By the time I settled at my classroom desk, I

was not interested in arithmetic, reading, or writing.

I was interested only in doing what I wanted to

do, and school didn’t make the list.

Mrs. Georgia Bulson, my classroom teacher,

was interested in me. She saw potential in all of

her students, including the sleep deprived. She

encouraged us, believed in us, pushed us, and entertained us.

My favorite moments in class included sitting on the classroom rug

while she read Nancy Carlson books in an animated fashion. I was

a challenging student, and in return, Mrs. Bulson challenged me

to learn and be engaged. For example, I didn’t qualify for gifted

and talented programming, but I showed enough spunk, energy,

and talent in pushing back against school that she found a way to

redirect my energies. She made a deal with me: If I did my work

in class, she would let me join Omnibus, the gifted and talented

class. I was ecstatic. My self-esteem soared. I felt smart, relevant,

and important. I helped to create the heady Omnibus newsletter, a

good challenge that was both fun and exhilarating.

Mrs. Bulson singlehandedly changed my seven-year-old life. At

the end of the school year, I was preparing to move to South Minneapolis

with my family. Mrs. Bulson stopped me as I exited the classroom

for the last time. She said, “I want to stay in contact with

you.” That was the beginning of a lifetime friendship.

The following school year, I started third grade across the Mississippi

River in what seemed like a foreign land. I was shocked and

disheartened that my new teacher didn’t meet the standards set

by Mrs. Bulson. One day, I phoned Mrs. Bulson with my concern. I

said, “My teacher thinks I am dumb.”

She said, “Why do you think that? Do you do your homework?”

I said, “No, but can you talk to her?”

That was one of many conversations spanning childhood, adolescence,

and adulthood. We went from yearly summer lunches to

yearly phone calls and greeting cards to stay in touch. I still refer

to her as Mrs. Bulson, my second grade teacher, although she often

reminds me that I can now call her Georgia, my friend. When I deal

with children in my line of work, I channel Mrs. Bulson, so I, too,

can singlehandedly change the lives of children by helping them

reach their full potential.

© Michael McColl